Government Energy Spending Tracker

June 2023 update

About this report

The IEA Government Energy Spending Tracker, formerly the Sustainable Recovery Tracker, provides periodic updates on the latest approved policies and their expected fiscal contributions to energy. The latest update, issued in June 2023, focuses on tracking two types of spending policies:

- Clean energy investment support, including measures to support investment in energy infrastructures, renewables, electrification, efficiency, and supply chains in the energy sector; and

- Short-term energy affordability measures, which are aimed to help shield consumers and industries facing soaring energy prices.

The latest update to the Government Energy Spending Tracker policies database tracks almost 1 600 government financial measures from 68 countries, all of which are available in the IEA’s Policies and Measures (PAMS) database.

This report is part of the IEA’s support of the first global stocktake of the Paris Agreement, which will be finalized in the run up to COP28, the next UN Climate Change Conference, at the end of 2023. Find other reports in this series on the IEA’s Global Energy Transitions Stocktake page.

Key findings

- The June 2023 update of the IEA Government Energy Spending Tracker finds USD 1.34 trillion allocated by governments for clean energy investment support since 2020. Government spending has played a central role in the rapid growth of clean energy investment since 2020, which rose nearly 25% from 2021 to 2023, outpacing growth in fossil fuels in the same period. Around USD 130 billion of new government spending to support clean energy investments were announced in the last six months – among the slowest periods for new allocations since the pandemic. This slowdown may be short-lived, however, as a number of additional policy packages are being considered in the European Union, Australia, Brazil, Canada and Japan. The newest outlays identified are predominately aimed at boosting mass and alternative transit modes, low-carbon electricity generation projects and low-carbon vehicle sales. Among all measures tracked since 2020, direct incentives for manufacturers aimed at bolstering domestic manufacturing of clean energy now total to around USD 90 billion.

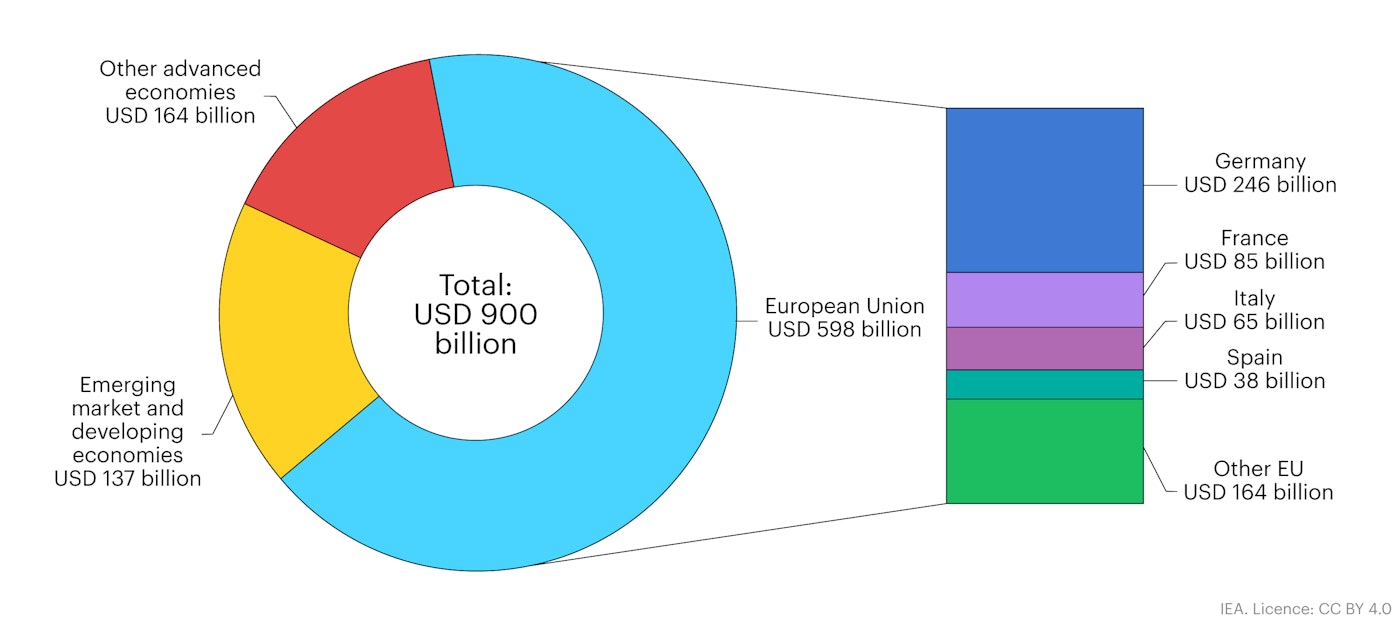

- Since the start of the global energy crisis, governments have also allocated USD 900 billion to short-term consumer affordability measures, additional to pre-existing support programmes and subsidies. Around 30% of this affordability spending has been announced in the past six months, and despite calls to better target households and industries most in need, only 25% of affordability measures are targeted towards low-income households and most-impacted industries.

- The European Union is responsible for two-thirds of government affordability support worldwide, having borne some of the steepest increases in electricity and gas prices in 2022. Levels of consumer support spending have also increased in emerging and developing economies, largely through governments compensating energy companies for operating losses borne by keeping prices stable during the energy crisis. As a result, governments in emerging market and developing economies have dedicated to date more to consumer affordability measures (USD 140 billion) than to clean energy investment support (USD 90 billion) since 2020.

- Emergency measures played an important role in shielding consumers from energy price spikes, but weighed heavily on government balance sheets, as fossil fuel subsidies reached an all-time record high in 2022. This could threaten some countries’ ability to balance short-term relief with parallel efforts to address energy security and affordability through improved energy efficiency and clean energy investment. This balance is particularly difficult in emerging market and developing economies due to pre-existing financial strains. Accordingly, the vast majority of spending on both affordability and clean energy remains concentrated in advanced economies, which now account for 93% of total government clean energy investment support and 85% of consumer affordability support tracked to date.

Explore the policies database

Browse more than 1 600 national government financial measures, spanning more than 68 countries, underlying the IEA Government Energy Spending Tracker.

Over the last 6 months, the global energy crisis has prompted a continued rise in emergency spending to manage affordability

Since the start of the global energy crisis, governments have allocated USD 900 billion to short-term consumer affordability measures. This affordability spending continues to climb, with over USD 270 billion allocated in the last 6 months, even as prices, notably in Europe, have begun to abate, albeit remaining well above historic levels.

New allocations for clean energy investment support totalled almost USD 130 billion in the past six months, making it one of the slowest periods of activity since Q2 2020. This runs counter to stated government intentions to accelerate clean energy transitions to manage exposure to global fossil fuel markets, notably plans like REPowerEU to drastically cut natural gas use this decade. However, a number of packages remain under discussion which could increase this total in the coming year.

The last six months continue trends seen since the start of the tracker, that the spending mobilised in advanced economies far outstrips that put forth in emerging market and developing economies (EMDEs). Advanced economies account for 93% of total government clean energy investment support and 85% of consumer affordability support.

Government spending for clean energy investment support and crisis-related short-term consumer energy affordability measures, Q2 2023

OpenAffordability spending loomed large in recent months, even as prices began to abate in wholesale markets. This tally captures all government enacted spending to help consumers manage prices, including direct grants, vouchers, tax reductions and price regulations. Announced government affordability measures often do not provide the full picture, as many pre-existing price regulations resulted in record levels of fossil fuel subsidies in 2022, which either continue to be tacitly borne by governments or state-owned energy companies, and often are felt as foregone revenues from not selling oil and gas resources at global market prices. The tracker does, however, capture government approved direct transfers from governments to energy companies to cover losses caused by mandated price regulations. In addition, governments also mobilised broader consumer supports to combat general inflation, which if considered, would also substantially increase the total.

Taken together, measures have been effective in shielding consumers from the price shocks seen in global fossil fuel markets, but still many households felt the crisis draw upon their finances. In 12 countries representing nearly 60% of the global population, average households saw their share of income going to home energy rise in 2022, despite substantial government intervention, as energy prices outpaced wage increases. Impacts were even larger for poorer households, as they typically spend a higher share of income on energy.

European Union countries are now responsible for two-thirds of total affordability measures. Germany is the largest single contributor to this total, and is estimated to be on track to spend around one-half of its EUR 200 billion economic shield (Abwehrschirm) budget envelope approved last October. Croatia, Poland, Italy and the Czech Republic represent the next largest new packages of affordability measures in the European Union. Outside the European Union, Australia made recent announcements in their 2023-2024 budget which, if adopted, would release AUD 3 billion1 towards energy price relief.

Government consumer- energy affordability measures, by region

Open

Spending by EMDEs on affordability measures increased in the past six months by additional USD 23 billion. These measures were largely in the form of direct transfers to energy companies for keeping prices at affordable levels through the early part of the energy crisis, as was the case in Indonesia, Mexico, Nigeria, and Malaysia. However, high oil and gas prices increased revenues for producers in these same countries, offseting their governments’ burdens to some extent.

The urgent need to accelerate investments in climate mitigation is adding to a global call for urgent reforms of MDBs, which would aim to restructure existing debt in EMDEs and increase the catalytic impact of MDB support to these countries. Leading to greater fiscal space and an increased focus on interventions that support private capital mobilisation through de-risking can help to increase clean energy investments in EMDEs.

Government clean energy investment support and consumer energy affordability spending earmarked by region, Q2-2023 update

OpenAffordability support is often made available to almost all consumers, instead of targeting those most in need

The tax reductions, fuel subsidies, energy price regulations, cost compensation or liquidity support measures offered to consumers and energy companies are largely not being targeted towards those most in need. Almost 75% of the amounts earmarked globally benefit the general population, as opposed to low-income households or economic sectors most exposed to energy cost increase. This indicates that calls in previous updates of the Government Energy Spending Tracker to better target support measures have not been entirely heeded.

Around 70% of global government spending on consumer affordability measures are going to support electricity, natural gas and heating. These measures were concentrated in Europe and Southeast Asia, to counteract high electricity and gas prices. In other countries, including many EMDEs, transport fuel prices rose more acutely, prompting EMDE governments to dedicate 65% of gather consumer supports to discounts on transport fuels. Other regions responded to higher transport fuel costs with reduced public transport fares, such as the launch of a fixed-price rail and regional bus tickets in Spain and Germany.

While these fiscal interventions are, in principle, meant to be short-lived, the lack of targeting raises questions as to whether countries are sending sufficient signals to consumers to reduce unnecessary consumption, increase efficiency, and seek out alternative energy supply. Some European governments have hinted at their intention to extend major support schemes until the end of next year, in anticipation of disrupted energy markets during the next Northern hemisphere winter.

Global government support for clean energy investment registers small uptick, but more could be on the horizon

In the last six months, outlays for new clean energy investment support increased by almost USD 130 billion, bringing the total enacted spending since 2020 to USD 1 343 billion. Government spending has played a central role in the rapid growth of clean energy investment since 2020, ending a multi-year slump in the late 2010s. In 2022, clean energy investment totalled to more than USD 1.7 trillion, meaning that for every USD 1 spent on fossil fuels, USD 1.7 is now spent on clean energy from public and private sources. Five years ago this ratio was 1:1.

New outlays are mainly for low-carbon electricity generation projects (now totalling USD 310 billion since 2020, mostly directed to renewable energy sources), mass and alternative transit modes (USD 307 billion), and low-carbon vehicle sales (USD 120 billion). Electricity grids have received the largest percent increase (reaching USD 85 billion); however, that still lags well behind other key areas.

The new Norwegian national transport plan, India’s Green Hydrogen Mission and Australian 2022-2023 budget were the largest new allocations, providing incremental funding for electricity grids, low-carbon power and electric vehicles (EVs). In addition, the Chinese government decided on the province-by-province allocation of its EV and renewable energy production schemes, which included more than was previously anticipated, after renewable support subsidies had declined rapidly in recent years.

Most EMDEs remain constrained by rising debt levels and limited fiscal means. However, a number of them have directed national development banks to support new clean investment, notably for green hydrogen and renewable power production projects in Chile and Brazil. New public-private partnerships are at the centre of Colombia’s new clean bus programme. In Middle East and North Africa, governments have supported state-owned companies to invest in new clean energy projects.

Government clean energy investment support enacted since the start of the Covid-19 crisis, by sector, Q2-2023

OpenA number of new policy packages are under discussion in the European Union, Brazil, Canada and Japan, which could materialise by the end of the Northern Hemisphere summer. Should the Canadian and Japanese packages come to fruition in their envisaged format, they alone could add around USD 200 billion to the global total.

Many of these packages are designed as direct responses to the United States’ Inflation Reduction Act (IRA), which still represents almost one-quarter of all clean energy support globally since 2020. Already, schemes to boost local clean energy production competitiveness are multiplying among advanced economies, mostly through calls for project or specific sectoral grants. The IEA estimates that direct manufacturer incentives since 2020 have reached around 90 billion of the total clean energy investment support since 2020; a clear sign that the global race for clean energy competitiveness is picking up. Recent examples include manufacturing incentives in Spain and Hungary for EVs, and in Romania for batteries. The Net Zero Industry Act recently put forward for discussion by the European Commission aims at ensuring that by 2030 two-fifths of the production of eight strategic clean energy technologies remains or develops in the European Union by fast-tracking permit delivery and allowing larger financial and regulatory support. The French government is also envisaging a Green Industry Plan to develop national low-carbon sector manufacturing capacity. Canada’s 2023 budget, currently under discussion, encompasses a new clean technology manufacturing investment tax credit scheme.

A similar trend can be identified among EMDEs. Some of them previously established domestic production incentives – such as India’s Production Linked Incentive Scheme, or the New Energy Automobile Industry Development Plan in the People’s Republic of China (hereafter “China”). In South-East Asia, the Malaysian Government introduced new income tax incentives for EV charger manufacturers operating in the country. The Thai government aims to boost local EV battery production and bring down the price of EVs on the domestic market through a new subsidy scheme. Trade policy instruments are also being mobilised: in January, the Philippines enacted a 5-year reduction in import tariffs, notably targeting EV components. More such incentives are on the horizon, including indirect incentives, such as local content requirements to qualify for investment incentives. The IEA will closely monitor these incentives in its upcoming updates.

Key government clean energy investment support policies added to the IEA Government Energy Spending Tracker database

|

Sector |

What is included? |

Total government spending enacted |

Common policy types employed |

Challenges |

Selected measures added since December 2022 update |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Low-carbon electricity |

Solar, wind, bioenergy, hydro, nuclear, and other renewable power. |

USD 310 billion |

|

|

|

|

Fuels and technology innovation |

Hydrogen, Carbon-capture sequestration, batteries, small modular nuclear reactors, other digital technologies, biofuels, biogas, and methane leak prevention. |

USD 182 billion |

|

|

|

|

Mass and alternative transit |

Mass transit, rail, urban buses, charging infrastructure, walkways and bikeways. |

USD 307 billion |

|

|

|

|

Low-carbon vehicles

|

Electric and efficient passenger vehicles, light and heavy trucking, shipping and aviation. |

USD 120 billion |

|

|

|

|

Energy-efficient buildings and industry |

Energy efficiency retrofits (buildings and industry), efficient appliances, near net zero new buildings, end-use renewables (e.g. solar thermal, geothermal). |

USD 264 billion |

|

|

|

|

Electricity networks |

Transmission, distribution, grid-side batteries, smart grid investment. |

USD 85 billion |

|

|

|

|

People-centred transitions |

Just transition mechanisms, worker training programmes, research programmes on market and social transitions. |

USD 20 billion

|

|

|

|

|

Energy access |

Access to clean cooking, electricity access by grid extension, minigrids, or stand-alone power systems. Basic, efficient appliances. |

USD 14 billion

|

|

|

|

Explore the policies database

Browse more than 1 600 national government financial measures, spanning more than 68 countries, underlying the IEA Government Energy Spending Tracker.

Methodology

The Government Energy Spending Tracker analyses disbursements made by central governments, from the second quarter of 2020 to 28 April 2023. Estimates are based on official government sources and their related budgets, when available, and on IEA analysis when spending volumes are not provided. The OECD released their assessment of energy affordability support measures, which differs in scope, and includes sub-national policies, affordability support beyond direct energy interventions, and assesses over a different time frame. This assessment can be found at:, “Aiming Better: Government Support for Households and Firms During the Energy Crisis”, OECD Economic Policy Papers No. 32, OECD.

Government clean energy investment support

Government clean energy investment support policies are defined as measures meant to drive spending on clean energy investment support included in government economic recovery plans in response to the Covid-19 pandemic or to the subsequent global energy crisis.

Common clean energy investment support policies include consumer or producer subsidies to develop electric vehicle markets, direct spending or Public-Private Partnership for building low-carbon and efficient transport infrastructures, grants for emerging energy technology pilot programmes, or tax incentives for energy-efficient building renovations.

Quantitative estimates in the Government Energy Spending Tracker are based on national-level clean energy sector policies enacted by governments from the second quarter of 2020 until end April 2023 as part of Covid-19 related recovery measures and directed toward long-term projects and measures to boost economic growth.

The Government Energy Spending Tracker organises clean energy investment support on a sectoral and regional basis, into seven key sectors: low-carbon electricity, electricity networks, mass and alternative transit, low-carbon vehicles, energy-efficient buildings and industry, cleaner fuels and emerging low‐carbon technologies.

Short-term consumer affordability measures

Short-term consumer affordability measures were enacted by governments in response to the international energy price rise that materialised in the fourth quarter of 2021 and was further aggravated by the Russian Federation’s (hereafter “Russia”) invasion of Ukraine. The most common policy instruments include temporary consumer subsidies or tax alleviation/exemption, state-backed loans or price regulation mechanism, often enacted as temporary measures.

The spending is assessed from the government’s perspective, as direct budget allocation, foregone tax revenues, etc.

Quantitative estimates from energy crisis response policies are based on policies enacted by governments from September 2021 to the end of April 2023, and are derived exclusively from official government estimates of the total direct cost of supporting those measures borne by governments. Accordingly, it does not capture other forms of implicit price subsidies that may be channelled through public utilities and other energy-related state-owned enterprises.

Collection process

The IEA independently collects government energy spending policies, in cooperation with its members, as well as G20 members. The full list of policies considered in the Government Energy Spending Tracker, including budget information, is available on the IEA Policies and Measures (PAMS) Database, a unique repository that has aggregated energy policies over the last 20 years, bringing together data from the IEA Energy Efficiency Database, the Addressing Climate Change database, and the Building Energy Efficiency Policies (BEEP) database, the IEA/IRENA Renewable Energy Policies and Measures Database, along with information on CCUS and methane abatement policies. These policy records include concise summaries of the policy, links to the original source, and relevant tagging for policy type, technologies and sectors.

About the tracker

The Government Energy Spending Tracker assesses the level of new commitments for government direct spending flowing toward energy. The update of the Tracker accounts for such spending since April 2020 to the end of April 2023.

The Tracker relies on extensive policy analysis conducted by the IEA. It includes around 1 530 energy-related government policies and spending programmes from 68 countries through the Policies and Measures (PAMS) database. All government spending allocated to energy sustainability and affordability policies as of 1 September 2022 was incorporated into the Global Climate and Energy Model for analysis in the World Energy Outlook 2022 in the Stated Policies Scenario, which provides an assessment of how this government spending contributes to rising levels of clean energy investment. All new policies captured since then will be included in the forthcoming World Energy Outlook 2023 Stated Policies Scenario.

The Government Energy Spending Tracker measures two types of energy spending: clean energy investment support and consumer energy affordability measures.

- Clean energy investment support includes all government spending that directly underpins increasing levels of clean energy investment.

- Consumer energy affordability measures includes all measures intended to help consumers and enterprises weather high energy prices in light of the global energy crisis. This category includes policies enacted by governments in response to the international price rise that materialised in the fourth quarter of 2021 and was further aggravated by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

The IEA also tracks fossil fuels consumption subsidies via a price gap methodology.

The 2022 IEA Global Energy and Climate Model documentation provides additional information on policy collection specifics for government recovery spending.

The IEA Government Energy Spending Tracker was initially published as the Sustainable Recovery Tracker on 21 July 2021, as requested by the G20 Rome Leaders’ Declaration, and the Joint G20 Energy-Climate Ministerial Communiqué. It benefitted from the support of the Italian G20 Presidency and is currently supported by the IEA Clean Energy Transitions Programme.

References

Exchange rate: 1 Australian Dollar (AUD) = USD 0.69

Reference 1

Exchange rate: 1 Australian Dollar (AUD) = USD 0.69